People frequently ask how often I spend months investigating something only to hit a dead end. My answer: Rarely. While investigative reporting is by nature risky business, there are steps you can take at the start to improve the chances of delivering at the end. Here’s an excerpt from an IRE Journal article I wrote while the Washington investigative editor at the Los Angeles Times that outlines a strategy for evaluating and testing project proposals before committing significant time and resources.

Plot it.

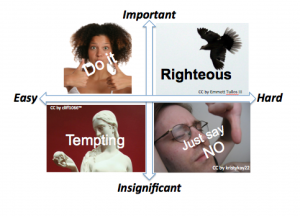

The greater a story’s importance, the more time and resources I might be willing to invest in it. So I use a simple graph to plot the relationship between significance and difficulty. While this is usually a mental exercise, plotting the proposal on paper with the reporter might be useful too.

Projects that are important – yet easy to nail – fall into the upper left corner. Important but difficult to prove? Upper right. Easy but of minor import? Lower left. Tough work that’s inconsequential to readers? “Just-say-no” territory.

Projects that are important – yet easy to nail – fall into the upper left corner. Important but difficult to prove? Upper right. Easy but of minor import? Lower left. Tough work that’s inconsequential to readers? “Just-say-no” territory.

The graph is a starting point for a discussion with the reporter. Deciding what makes a project proposal important will involve a fair amount of give and take. Does the problem waste thousands of tax dollars or millions? Does it affect a hundred people or a thousand?

Once the project is charted, you may decide to go ahead with an insignificant but easy story because it’s an exceptionally good yarn. At the other extreme, you may want to do a reality check before embarking on an important project that is exceptionally difficult. This sort of analysis also may help choose between competing proposals or to assess whether to add time and resources to an ongoing reporting effort.

Alan Miller brought two great project ideas to me a few years ago. They both looked challenging yet important enough to justify considerable time and effort. But he could not undertake two major projects at the same time. After he did some scouting on each of them, we concluded that the first proposal involved the threat of serious harm, while the second involved actual and ongoing harm. Actual harm scored higher on our “importance” scale. So ultimately we went with that one. We made a good decision. Miller and Kevin Sack produced a Pulitzer Prize-winning series on the deadly track record of the Marine Corps’ Harrier jet.

Test it.

Make a list of the basic facts that must be proved before a story can be published. Identify which of these make-or-break facts is easiest to prove, and check it out first. If true, move on to the next fact. If false, move on to the next story idea.

We went through that drill when Ken Silverstein and Chuck Neubauer pursued a tip that the daughter of U.S. Rep. Curt Weldon (R-Pa.) had been hired to lobby for East Bloc businessmen receiving political favors from her father. Both reporters receive many more promising leads than they can ever tackle. So we are always looking for the most economical way to weed out the bad from the good.

In this case, we identified three baseline questions and some likely places to find easy answers:

1. Was Weldon’s daughter a lobbyist? State corporation records, federal lobbyist registration records, federal foreign agent registration reports, clips.

2. Did she have East Bloc clients? Federal foreign agent registration reports.

3. Had Weldon done political favors for them? Congressional Record, press

releases, clips, foreign-agent registration reports.

Neubauer and Silverstein decided to check the foreign-agent registration reports first. The law requires lobbyists, public relations consultants and others to provide the Justice Department with names of foreign clients and services provided to them. The reports are available without a Freedom of Information Act request. The office is just a short walk from our Washington bureau, and the reporters figured they might find answers to all three questions there. In fact, the reports confirmed all our baseline facts and provided intriguing leads that guaranteed this would be a successful project.

As a reporter in Seattle, I had a messy pile of tempting leads on my desk, when I received an anonymous tip that two local tribal officials had built a 5,300-square-foot house for themselves through a federal low-income Indian housing program.

As with the other leads, I quickly mapped out the essentials:

- ls there a big house?

- Is it owned by the tribal officials?

- Was it built through a federal low-income housing program?

Seemed to me the easiest first step was to see if a big house sat where the tipster said it did. So I drove to the reservation.

After passing tracts of tiny houses and old trailers, I found the luxury domicile – and one of the tribal officials. He admitted that he owned it with his wife, who ran the tribe’s housing office. He also told me their house was financed through a bank and not through a federal low-income housing program. Even so, I’d confirmed in less than three hours that two out of three of my essential elements were true. That gave the tip enough credibility to justify spending a little more time to determine if he was telling the truth about the financing.

A subsequent FOIA response showed that the tipster was right on all counts – and the house might be part of a national pattern of abuses in HUD’s tribal housing program. The project grew from there into a nine-month investigation with two other reporters that produced a Pulitzer-winning series.

Launch it.

THE basic WHAT-WHY-WHEREFORE INVESTIGATION REPORTING PLAN

WHAT: Document the problem What happened? How many affected? What consequences? Examples?

WHY: Determine the cause What and who are responsible?

WHEREFORE: Identify the solution And why isn’t it getting fixed?

- You have critical mass.

- The reporter has stopped making significant forward progress.

- External events – news events, competition – require you to publish.

Video: National Press Foundation | “‘Shock and Awe’ — How to Dig Up the Real Story”

— Deborah Nelson

1 comment

Hi, Deborah. I am teaching investigative reporting at a university without many resources for journalism. My students want to learn long-form writing, and I want to teach them things I think they can use in the future. I’d like to focus on reporting and writing to uncover the truth. Do you have any suggestions? Should I have them choose a national problem with local nuances and then the whole class or teams work on it? Could I ask each one to do that but make the project focused on one angle of corruption or dire need? I teach feature writing and storytelling in public and private spaces as well as law, ethics, and history. If you have time to offer suggestions, I’m all ears. I love the idea of my students digging out facts and making a case to tell the public the truth. Our successes in long-form writing this year include getting one young woman to Ghana to research education problems there face-to-face for three to five narrative articles she is writing. She sent the query letters already. We also are sending a young man to Washington, D.C., to participate in the Political Journalism Institute. I helped them both find funding for their projects, and I work closely with them on their writing. I am hoping our long-form classes can take more students to places they want to go to do in-depth reporting and narrative journalism writing. Take care, Paulette